the tree-shake mystery - part 1

Note: This is an old post, rewritten for documentation and clarity.

When building an NPM library or application, we should always (apart from providing TS types for auto-completion) build our code that allows it to be tree-shaken.

Tree-shaking is a deadcode elimination process done by a bundler (eg. webpack, rollup etc) when building an application or a library.

TLDR; tree-shake is not the only thing we should be looking at to optimize our code.

Lets 'kupas' this further

Consider the following code:

export const plus = (a: number, b: number) => a + b

export const minus = (a: number, b: number) => a - bWe are exporting (2) functions plus and minus from math_helper.ts. Now, lets import (1) of the function:

import { plus } from 'math_helper'

plus(1, 2) // 3If our bundler is not configured for tree-shaking, our final build for app.ts will contain both plus & minus, even though minus is never imported. This is what we call deadcode.

Deadcodes are codes that are shipped to the client, but never gets executed. A classic example of this would be importing lodash the old-fashioned way. Lodash contains hundreds of helper functions to deal with strings, arrays etc. But if the project only uses 2-3 helpers, we will still ship the rest of them in the final build!

So, how do we stop this deadcode madness?

Bundlers place ESM support as requirement to achieve tree-shaking

In the case of lodash, the library has been rewritten with ESM support (lodash-es), so bundlers can safely tree-shake even with this import statement

import { get } from 'lodash-es'However, the better solution is to import the helper function exclusively. This way, even without tree-shaking, the final build will only contain the imported helpers and nothing else:

import get from 'lodash/get' // File with single export functionThis makes a huge difference in the build size. In my career, I have seen production app with >3-5MB size, bundled into a single JS file, which is insane. And you guessed it, majority are deadcodes. Of course, the problem is more than just tree-shaking when you have an app size that big (eg. code-splitting, lazy-loading etc).

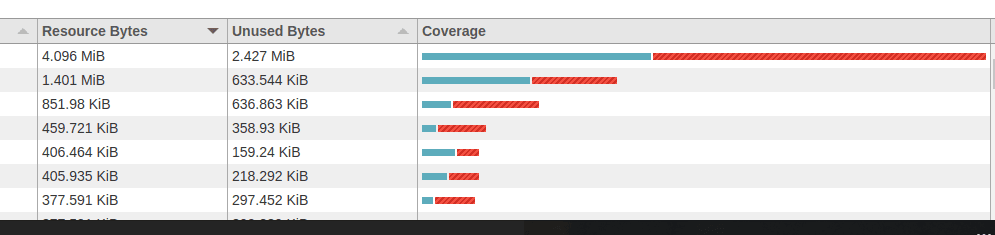

How to determine deadcodes?

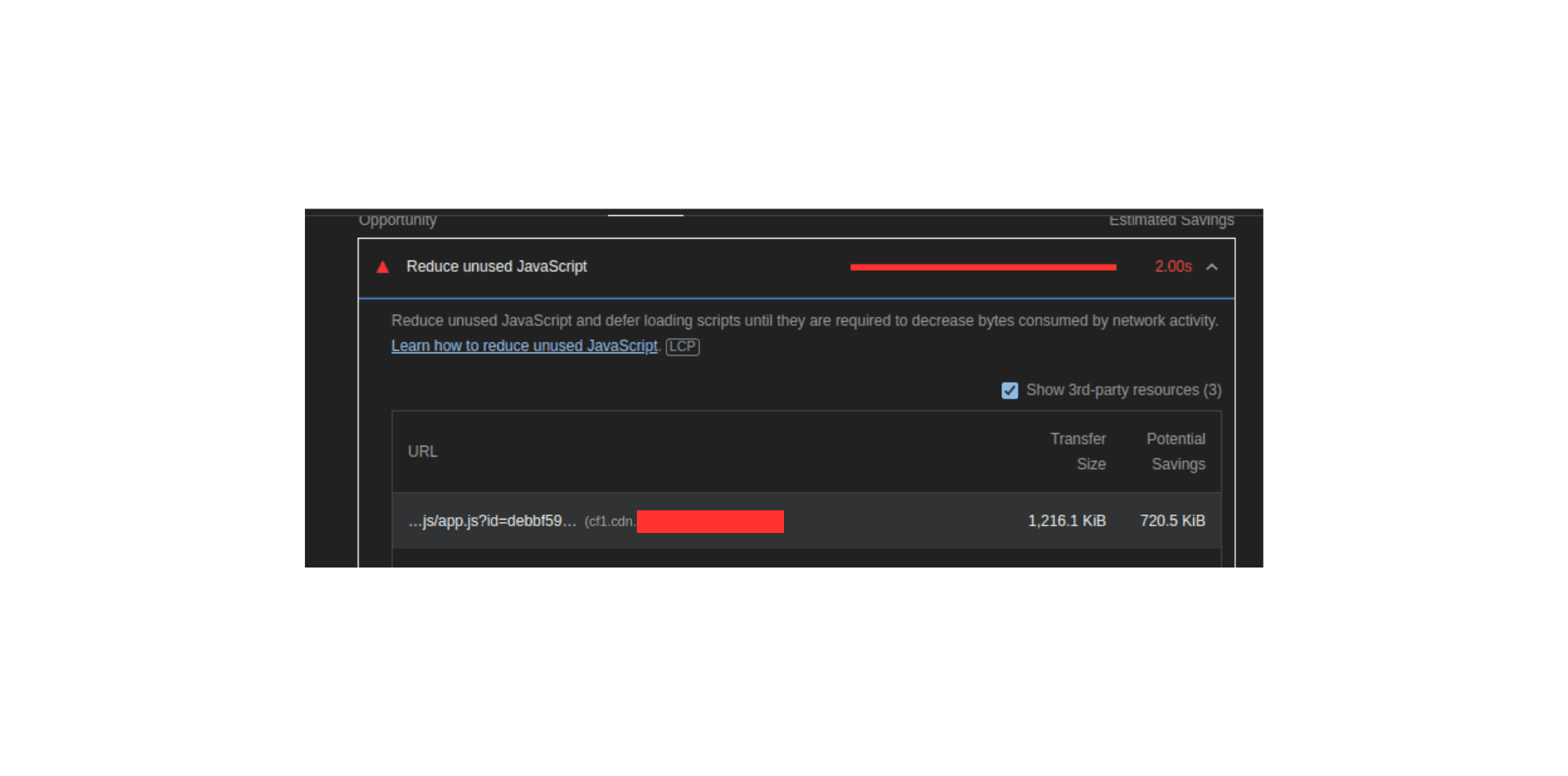

The first step is to check the Lighthouse report. You can find it in the dev tool in any Chrome-based browser and run the diagnostics. After that, click on View Treemap and you will find a chart like below:

Look at that code coverage 💀💀💀.

Ok, next:

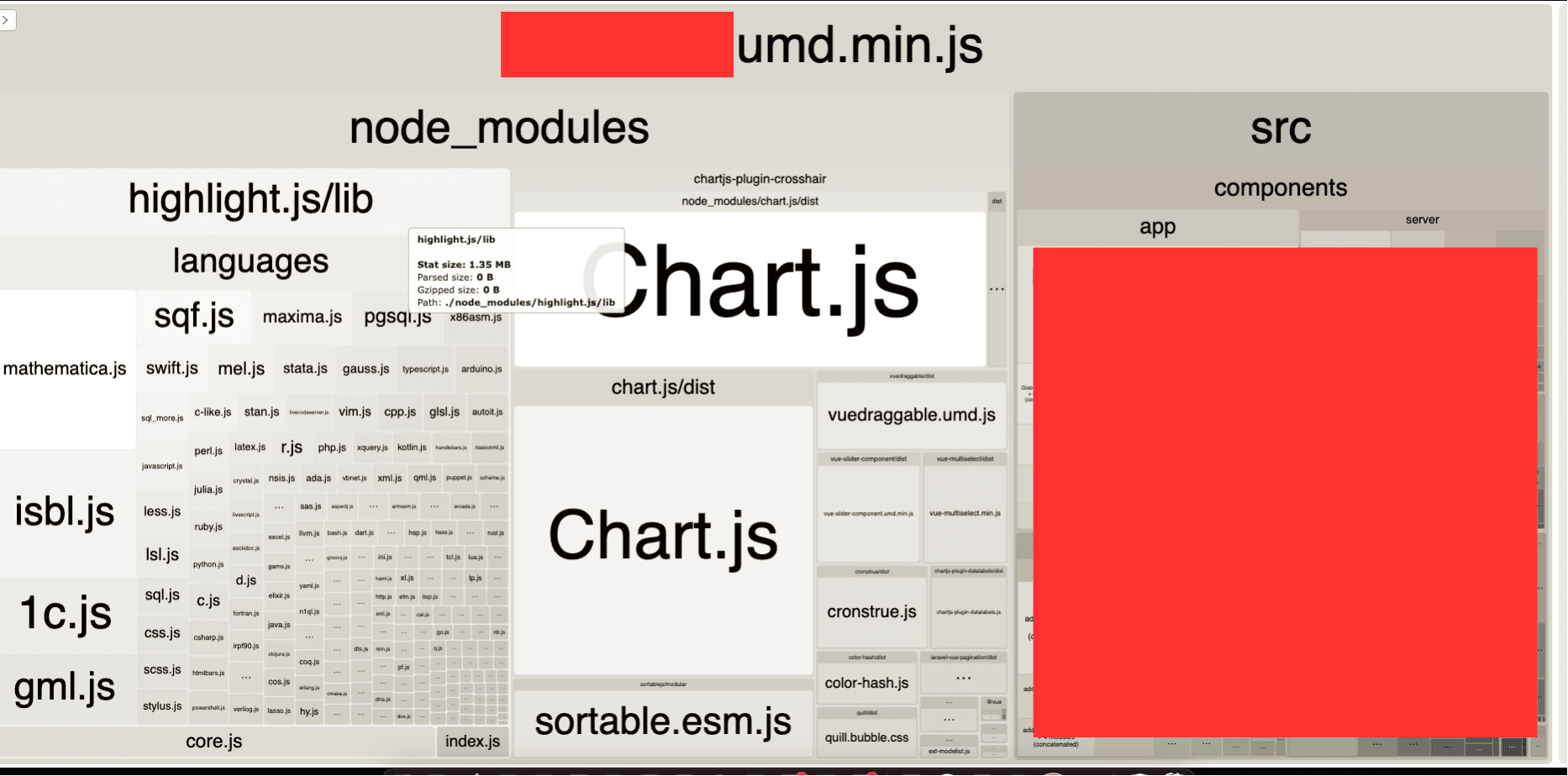

If you are using webpack, install: Webpack Bundle Analyzer (opens in a new tab)

If you are using vite or rollup, install: Rollup Plugin Analyzer (opens in a new tab)

This lets you know the composition of what goes into the final build. I'll show you an example of what I worked on before:

One module alone - highlight.js takes 1.35MB! As mentioned earlier, the problem with this particular example is not just about tree-shaking, but simply, how unoptimised it is written.

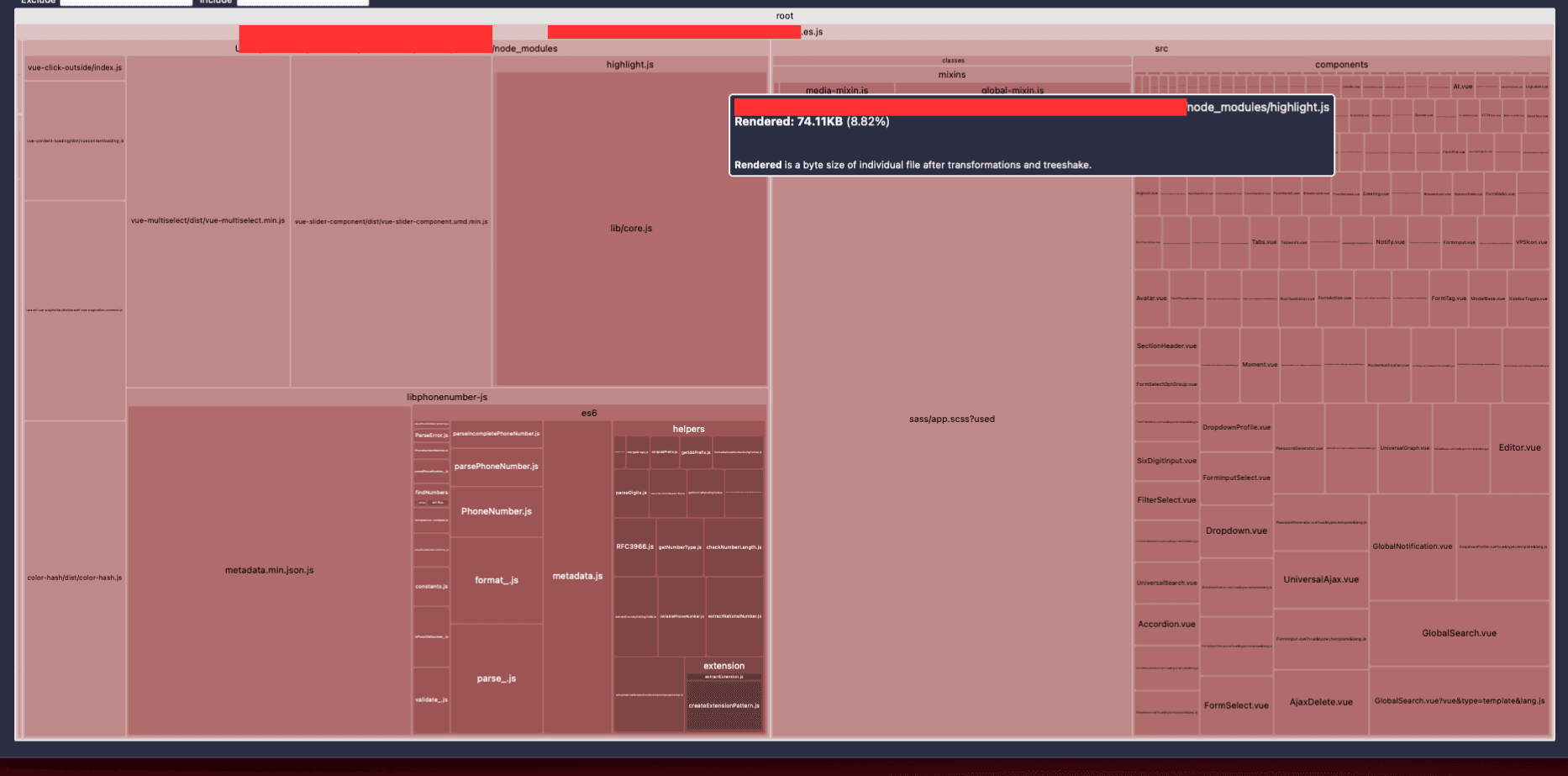

After implementing lazy loading, I was able to cut down highlight.js from 1.35MB to a mere 74kB and lazy load the styles & language syntax as necessary at runtime.

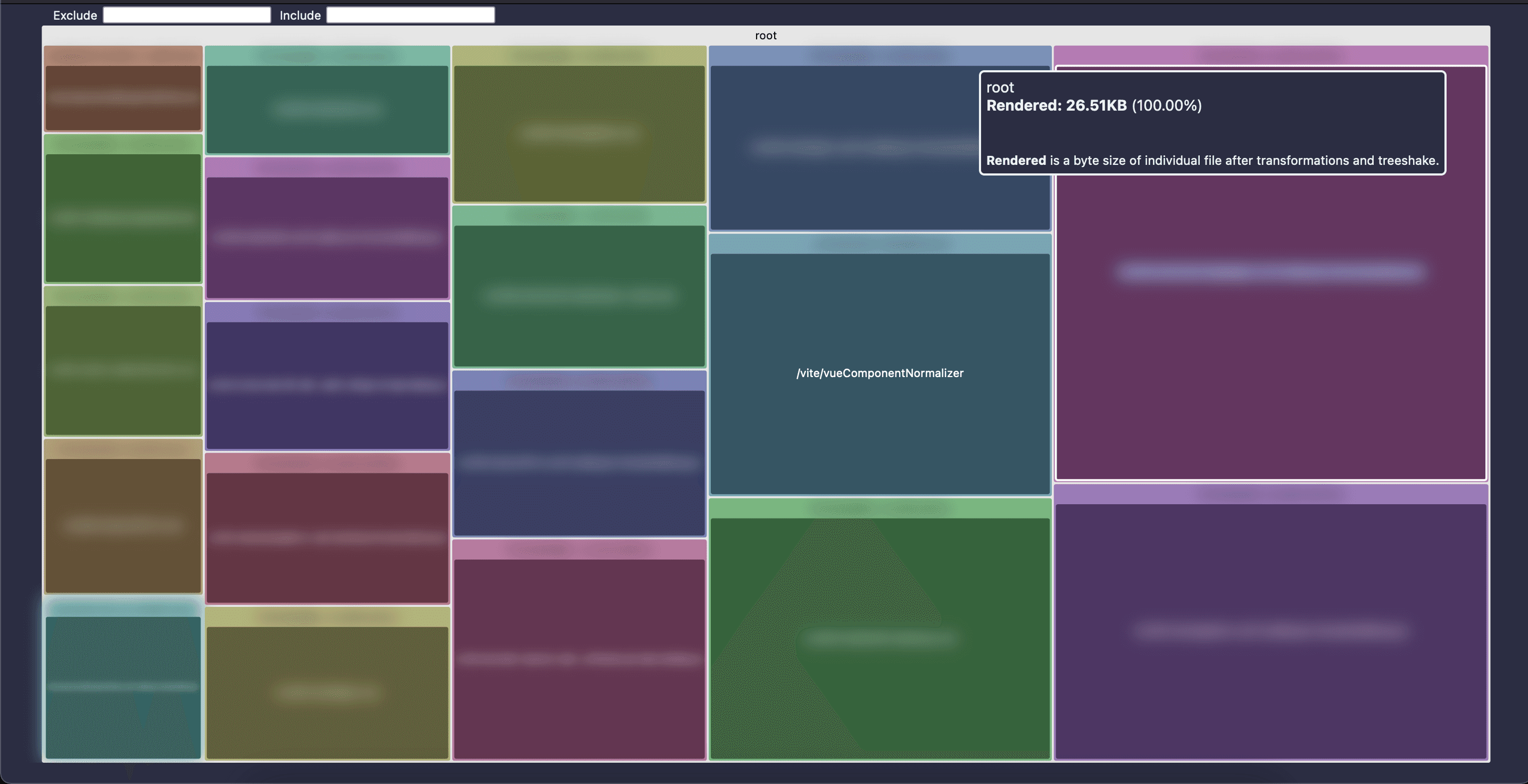

After this, I implemented tree-shaking to the final build. However, the end result will be misleading. Mainly because, in this exercise, I am converting components from a project and turn it into a UI library. So, certain modules are made as peer-dependency, which means, the modules are intentionally removed from the final build and would be imported at the project level. But anyways, here it is:

This is one of the modules built, and it only takes 26.51kB. There's actually 4 more of these at various sizes haha.

And if I'm not mistaken, the final build at the project level ends up at 1.2MB. (60% reduction in build size)

Conclusion

Tree-shaking is one of the mechanism bundlers have, to cut down unnecessary weight at the final build. However, it's not the only mechanism AND certainly not the one that you should depend on to optimize your code.

The bulk of bundle optimizations are done through other means, such as lazy-loading, code-splitting as demonstrated earlier.

However, as a developer, the bare minimum is to understand how libraries are being imported and the underlying process that goes into bundling it. In Part 2, I will expand further on tree-shaking best practices, so stay tuned.

© Irfan Ismail.RSS